Allyson Bear, the vice president for health programs at IMA World Health and Lutheran World Relief, recently travelled to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where she observed the response to the outbreak of Ebola in the country’s North Kivu region.

As my IMA World Health colleagues and I pulled our suitcases through the Rwanda border to the Democratic Republic of Congo immigration building, the Ebola response was noticeably present. White marked U.N. personnel carriers and fuel trucks were lined up to cross the border. We washed our hands at chlorinated water stations. We had our temperature taken and recorded three times at different points between the buildings, and we applied and reapplied hand sanitizer every few yards. None of these measures were optional.

The city of Goma sits on the north coast of Lake Kivu and comes right up to the immigration point. Being at high altitude on the equator, the weather is perfect year-round. The lake is warm and enormous. It might as well be the ocean. The sun sets every night over the mountains to the west, which is a rebel-held jungle. Everybody suffers there. At night mineral resources are reportedly trafficked across the lake to Rwanda in exchange for guns to fuel the rebel activity. The beauty of Goma masks its great tragedy —this part of DRC hasn’t seen peace in 25 years. An estimated 5.4 million people have been killed since 1994, and 3 million remain displaced today.

At the U.N. Ebola Emergency Operations Center in Goma, there is a well-attended briefing each morning at 8:30 a.m. that serves to coordinate the work of several U.N. agencies, Congo’s Ministry of Health, U.S. government agencies and numerous international nongovernmental organizations. Everyone’s temperature is taken on the way into the U.N. compound, and everyone is administered two pumps of hand sanitizer. People greet each other with an elbow bump rather than a handshake, practicing the same infection-prevention techniques they spend their days promoting to communities.

Dr. William Clemmer, right, of IMA World Health and Lutheran World Relief, demonstrates the elbow bump greeting with a colleague.

On this day we learned there were seven cases of Ebola confirmed the previous day. We collectively reviewed each case. One was a 2-year-old boy who had been in and out of hospital facilities for almost two weeks due to a series of misdiagnoses. He died the day he was confirmed to have Ebola. Each case was unique, each had a different journey that led to their diagnosis. Some were “high risk” cases — which means they were known close contacts to other Ebola cases. Some died at home and were only diagnosed posthumously. This is a major challenge to getting this epidemic under control.

Despite an enormous and robust response by the international community, half of all people who die of Ebola die at home, never having sought medical treatment. Despite an effective vaccine and effective treatment protocols at Ebola Treatment Centers, some people are still refusing the vaccination, hiding from health care workers or running away from isolation facilities.

The rate of mortality from Ebola in the DRC outbreak is a moving target, but it hovers around 65%. The mortality rate is much lower (around 30%) among people who arrive early to the Ebola treatment centers. DRC is benefitting from the knowledge gained from the West Africa outbreak, and people who are diagnosed early are likely to survive; but the overall mortality rate remains high because people delay or never seek treatment from the health system. Over 50% of Ebola cases never present themselves to the health care system. They are being cared for at home by relatives and are only identified through a very rigorous effort to administer a post-mortem test on each body in the Ebola zone.

Having relatives caring for Ebola patients is very dangerous. Many households have limited access to enough water for basic cooking and cleaning. The efforts needed to sanitize a house and to take good infection prevention measures are beyond the knowledge or capacities of many households in the Ebola zone. The consequence is what we saw with the recent cases that crossed over into Uganda in June 2019. A woman with two small children had traveled to DRC to care for her ailing father, who was a pastor. He eventually succumbed to Ebola at home and was buried. By the time the extended family began their return journey back to Uganda, they were exhibiting symptoms of Ebola. They were put into isolation at the border for evaluation and transported to an Ebola treatment center. Presumably with the idea that they could get better care in Uganda, the woman and her mother escaped the isolation unit with the two young children and crossed the border on a footpath. Not only have they all since died, but 97 people within Uganda came into contact with them before they were identified as suspected Ebola cases and isolated.

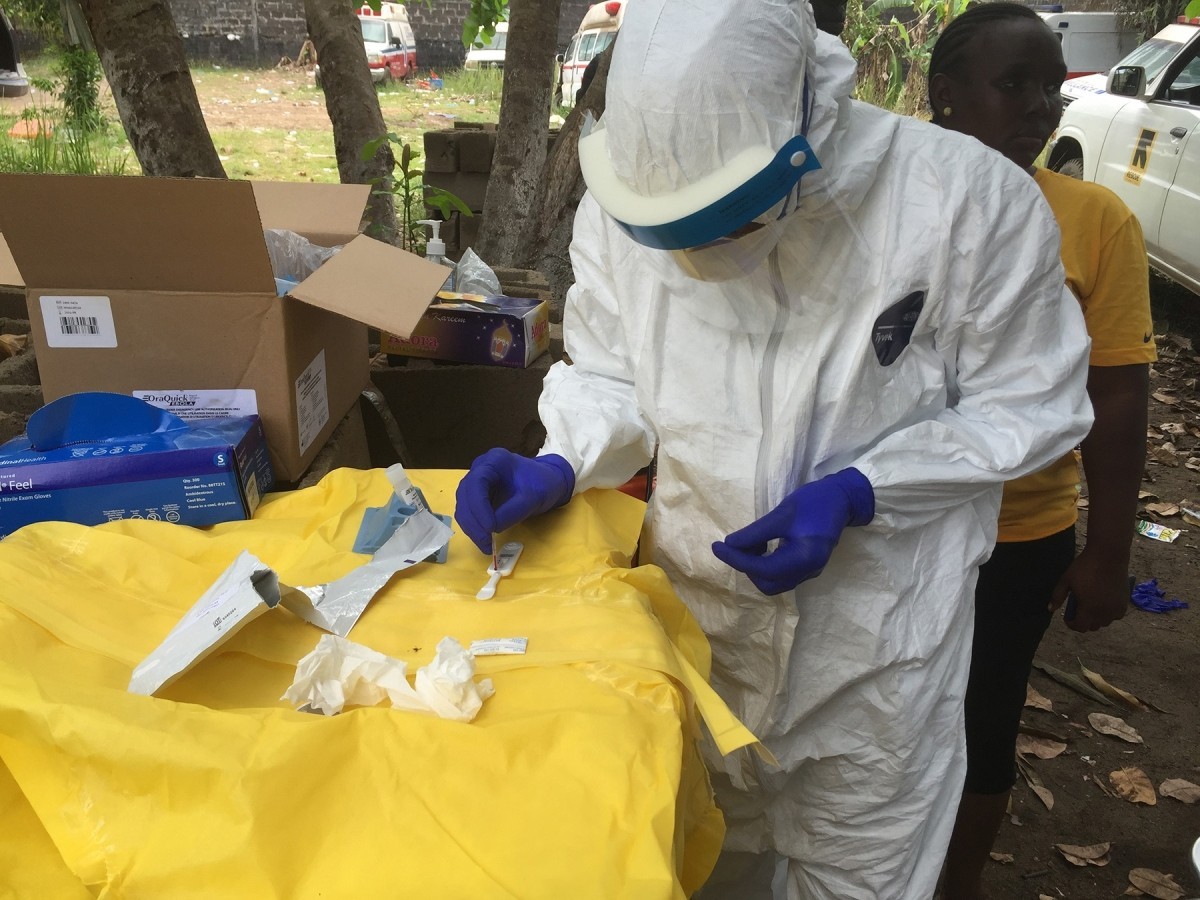

While in the field, dressed in personal protective equipment (PPE), this epidemiologist conducts a rapid diagnostic test, which was used during the Ebola response to quickly test for the presence of Ebola virus. (Photo by John Saindon for CDC)

The rest of our time in Goma was spent with our local partner, HEAL Africa, and an international partner with whom we have a great collaboration, Tearfund. Sitting together, we thought through how much we could reasonably scale up in order to mobilize an effort to keep Ebola from reaching Goma, a city of 2 million people. Ebola would take off in a dense urban environment like Goma, and controlling it would be much more difficult than in the relatively rural areas of North Kivu. Our desire to mobilize the most robust response was tempered by our capacity to ensure good oversight over the facilities we would support. One stumbling block for us is the main road connecting the outbreak zone and Goma is very dangerous, and this is precisely the area where we need to work. The road runs through a national park that harbors myriad rebel groups and bad actors. The only way through is by convoy, arranged by the park guards at each entrance. This is the zone we are preparing to move into. During our meeting, much of our conversation focused on what adaptive and innovative approaches we could take to ensure our work is well done while also ensuring our staff are safe.

Presently IMA World Health supports 76 facilities in Butembo, Beni and Goma. In these facilities we provide training to health care workers on how to protect themselves from Ebola infection. We reorganize the clinics to set up screening, triage and isolation units so that suspected cases are separated from the general patient population as soon as possible. We ensure facilities have enough water to properly sanitize the facility and wash hands and equipment. We provide chlorine, soap, bleach, gloves and other basic supplies to reduce the likelihood of spreading Ebola within a health clinic. And we have equipped health care workers with protective equipment — the white or yellow outfits that look like space suits that you have seen in the news. We work with community workers to keep an eye out in their communities for families that may be caring for a sick person. We visit our facilities three times a week to make sure they have the supplies they need and address any problems they might have. And we report everything that happens in the facility to the U.N. Emergency Operations Center for aggregation. This level of engagement with local health facilities takes an enormous amount of effort. However, IMA is committed to this model because it builds the capacity of the existing health system.

IMA World Health partner Tearfund staff meet with congregations and youth groups in Butembo.

Ebola will not be in North Kivu forever, but the facilities we are supporting will retain the water facilities we have supported, and the health care workers will retain the skills to protect themselves from deadly infectious diseases long after the Ebola response has ended. At IMA we say that we use development approaches in emergency response settings. Our work in the Ebola zone is exactly what we mean. IMA has three employees working in the Ebola zone, and we work through a local partner to implement our activities. Our staff sit in their offices, working side by side to control this outbreak. We “lead from behind,” supporting local partners and the Ministry of Health to perform their mandate in ways that will bring this outbreak under control. In the end our local partners will be stronger, the Ministry of Health local personnel will be better able to perform their functions overseeing the health system, and IMA will effectively “work itself out of a job.”

That is the vision we have for a post-Ebola DRC. Until that time, we are with the people of Eastern DRC. We will walk this journey with you. We will support you during your time of crisis. And we will rejoice with you when you emerge from these dark days, stronger and more resilient than ever.